Does intelligence require a body?

Does the body have an impact on how we think?

In our quest to comprehend the essence of intelligence, we often ponder the intricate connection between the mind and the body. Is the mind the puppeteer, orchestrating the body’s every move, taking it on exhilarating journeys of experience? Or, in a reversal of roles, does the body guide the mind, wielding the impulses of hunger, fatigue, and anxiety, akin to a river deftly steering a canoe? Perhaps the mind is more like electromagnetic waves flickering within the confines of our corporeal vessels, or it assumes the role of a car navigating the winding roads of consciousness — a perplexing ghost in the machine.

Renowned roboticist Boyuan Chen, delving into the realm of intelligent robotics at Duke University, reminds us of the profound entanglement between the human mind and the body’s actions. This symbiotic relationship, honed over millions of years of evolution, underscores the fact that the mind, whether human or animal, is inextricably linked to the body’s responses to the real world. As human babies instinctively grasp objects long before acquiring language, the significance of this deep-rooted connection becomes evident.

Yet this intricate web of the mind and body has long captivated the realms of philosophy and science. At its core lies the enigmatic mind-body problem, a puzzle that probes the complex interplay between thought and consciousness within the human mind and the body. In everyday life, the mind and body appear to harmonize seamlessly — emotions like sadness evoke tears, and laughter naturally follows the perception of humor. The mind’s sensations of pain prompt the body’s avoidance mechanisms, illustrating their intimate cooperation. Changing the body’s chemistry with drugs or therapy methods like cognitive behavioral therapy can change how people think, which can have real effects on their health.

Despite the seeming simplicity of these mind-body connections, deeper contemplation begets profound metaphysical and scientific questions:

-

Are the mind and body distinct entities or facets of a unified whole?

-

If distinct, do they causally interact, and can such interaction be comprehended?

-

What characterizes this interaction, and can it be subjected to empirical scrutiny?

-

In the case of a unified entity, can mental events be elucidated through physical events, or vice versa?

-

Does the relationship between mental and physical events emerge at a specific developmental juncture?

Drawing inspiration from ancient wisdom, the Buddha, the sage behind Buddhism, offered an intriguing perspective on the intricate relationship between the mind and the body. He likened their interdependence to two sheaves of reeds leaning against each other, emphasizing their reliance on mutual support. According to Buddhist teachings, the mind manifests from moment to moment, akin to a fast-flowing stream within an ever-changing universe. In the ultimate realization of Nirvāna, all phenomenal experiences cease to exist, solidifying the philosophy that both mind and matter are conditionally arising facets of existence.

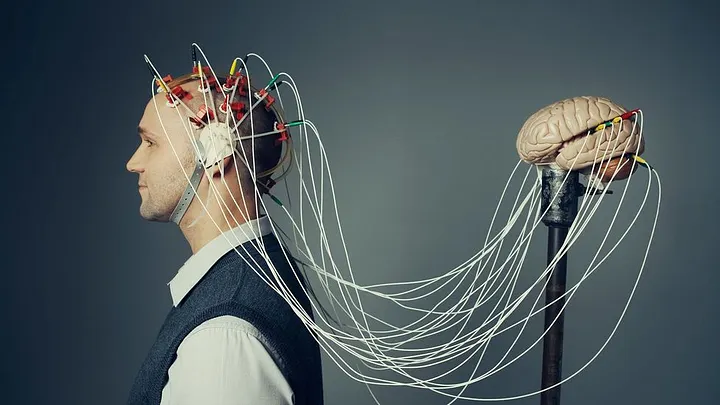

This age-old quest to decipher the mind-body relationship continues to challenge our understanding of human consciousness and existence, leading us on a captivating journey through philosophy, neuroscience, and artificial intelligence. However, recent scientific revelations have disrupted conventional notions of cognition, ushering in a new era known as ‘embodied cognition’. In this paradigm, psychologists explore how specific movements can influence memory recall, while neuroscientists investigate the role of the brain’s motor system in cognitive functions, including language comprehension. The field of artificial intelligence has also seen a paradigm shift, questioning whether the form of a machine impacts its capacity to exhibit intelligence.

The prevailing thought in the early days of AI, during the 1950s and 1960s, posited cognition as the manipulation of abstract symbols following explicit rules. However, modern insights suggest that cognition is more intertwined with the physical body than previously believed. In the age of ‘good old-fashioned artificial intelligence’ (GOFAI), it was assumed that the mind, like software running on computer hardware, was detached from the physical platform. But as we try to understand, the lines between the abstract and the physical keep getting blurry. This makes us think again about how important embodiment is for intelligence and consciousness.

Mind-body relationships are complicated. As we explore them, we find ourselves immersed in a deep exploration of how our bodies and the ethereal realm of thought interact with each other, raising questions about the very nature of human existence and intelligence.

Is thinking more than just symbolic processing? A Journey from Descartes to Embodied Cognition

In the ever-evolving landscape of artificial intelligence, we stand witness to the awe-inspiring strides made by chatbots such as OpenAI’s GPT-4 and Google’s Bard. These AI marvels exhibit a peculiar semblance of “minds” by generating a diverse tapestry of text, images, and even videos. They express desires, beliefs, hopes, and an impressive array of human emotions. Yet, a profound question looms among researchers: Can these machine “minds,” organized in modular structures, ever authentically bridge the gap with the physical world and encapsulate the quintessential facets of human intelligence?.

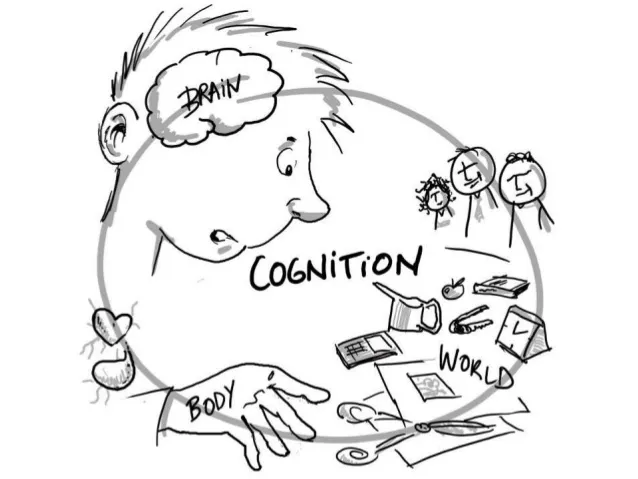

To unravel the intricacies of this enigma, we must embark on a journey into the realm of embodied cognition — an intellectual paradigm that accentuates the pivotal role of the body in sculpting cognition and comprehending an agent’s mind and cognitive capacities. This perspective stands in stark contrast to the classical Cartesian model, which posits the mind’s autonomy from the body, the world, perception, and action.

Embodied cognition asserts that cognition is not a solitary phenomenon but a tapestry woven from experiences derived from possessing a body replete with a multitude of sensorimotor capabilities. These capabilities are intricately woven into a broader biological, psychological, and cultural context. In essence, cognition in biological systems isn’t a detached process; it’s intimately entwined with the system’s objectives, capabilities, and interaction with the environment.

The classical Cartesian perspective, long dominant in Western philosophy, perpetuated the separation of mind and matter. However, recent years have witnessed cognitive scientists challenging this conventional wisdom. They propose an alternative view wherein the brain serves as but one component of a more expansive “mind.” This “mind” is conceived as a cognitive system deeply embedded within the organism’s physical framework and intricately intertwined with its surroundings.

This paradigm shift from the idea of a separate mind to an embodiment-based model of cognition has huge effects on many fields, from neuroscience to robotics to philosophy. It blurs the demarcation between mind and body, revolutionizing our understanding of human intelligence.

This concept of embodied cognition transcends basic animal activities such as walking and hearing; it extends its influence to higher-level facets of human intelligence. Recent research has unveiled captivating insights into how the physical environment can mold human thought processes. For instance, the act of wearing a white coat can sway decision-making, and merely holding a weightier clipboard can influence judgments regarding the “weight” of certain decisions.

Plato’s famed allegory of the cave depicted thinkers confined within, interpreting the external world by decoding shadows on the wall as representations of reality. Yet, this analogy falls short in capturing the intricate relationship between the mind and the external environment. Contrary to the traditional view of a mind barricaded from the world, contemporary cognitive science suggests that the mind is intricately entwined with the world it endeavors to comprehend.

As we navigate the ever-evolving tapestry of intelligence, these questions regarding the interplay between mind, body, and environment continue to mold our perception of what it means to be intelligent — whether in the domain of artificial intelligence or the profound realm of human cognition.

The idea that thinking involves the mere processing of symbols has a lineage tracing back to the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Visionaries like Copernicus and Galileo described nature in terms of geometric figures and mathematical formulas, laying the foundation for conceiving thought as fundamentally mathematical. While Thomas Hobbes envisioned reality as mathematical and therefore believed thinking was akin to particles, René Descartes postulated that thoughts represented symbolic representations of reality, separate from the physical body. This dualistic view of the world, distinguishing between the ‘mind’ and the ‘brain,’ persists to this day. In the early days of artificial intelligence, optimism reigned supreme, with luminaries like Herbert Simon envisioning machines capable of performing any task a human could within a mere two decades. Marvin Minsky, another pioneer in the field, proclaimed that the problem of creating “artificial intelligence” would be substantially solved within a generation.

This optimism thrived as long as artificial intelligence focused on problem-solving based on explicit rules — computation that involved abstract symbols. Computers excelled at chess, algebraic problem-solving, and text manipulation. However, when it came to simulating natural behavior — constructing robots capable of functioning in unfamiliar environments — traditional artificial intelligence floundered. The concept of providing a machine with sensors and motors while adhering to rule-based models proved inadequate, failing to match the agility of a cockroach.

Larry Shapiro, a professor in the Department of Philosophy at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, USA, aptly describes this earlier era, where early robots often had processors external to their bodies, akin to a brain in a vat. These “brains” operated separately from the body, processing sensory input, manipulating symbols, calculating outputs, and instructing the robot’s movements — a process characterized by sluggishness and susceptibility to environmental changes. The robot’s deliberation often lagged behind real-time shifts in the environment.

Prof. Rolf Pfeifer, who is a computer scientist and works at the University of Zurich’s Department of Informatics, says that it is hard to get out of the Cartesian worldview, which sees thinking as algorithms or computer programs. The notion of input, processing, and output seems irrefutably self-evident. However, insights from philosophy, psychology, neuroscience, and evolutionary biology have redefined our understanding of intelligence. When viewed through an evolutionary lens, it becomes apparent that brains have always developed within the context of a body’s interaction with the world, evolving as a dynamic response to survival requirements. Contrary to what traditional cognitive science claims, brains do not develop in an algorithmic ether. The past few decades have witnessed a profound paradigm shift, ushering in a new perspective on the nature of cognition.

Can robots learn and perceive like humans? The Power of Sensory-Motor Integration in AI

In the dynamic realm of artificial intelligence, we are amid a transformative era marked by the emergence of robots that bridge the gap between sensing and acting. These robots are designed to fuse their sensory perception directly with motor functions, departing from the conventional ‘sense–model–plan–act’ paradigm. This shift allows these machines to react swiftly and with greater precision as they process only the most relevant information. Such robots continually monitor their internal state and the external world, adjusting their actions accordingly.

This shift toward enhanced efficiency in machine movement transcends a mere objective; it might very well represent the initial steps toward attaining human-like artificial intelligence. To develop true machine intelligence, the machine must acquire its own experiences. As Giulio Sandini explains, human cognition is rooted in genuine experiences. Unlike the preprogrammed knowledge typical of Good Old-Fashioned Artificial Intelligence (GOFAI), embodied cognition advocates providing robots with sensory and experiential capabilities to learn through interaction with the world.

Children, for instance, learn about their environment through direct interaction, much like robots should. These interactions not only facilitate learning but also help in connecting experiences from various sensory systems. Through such interactions, a child learns to differentiate between objects, not solely based on visual input but also considering how they would interact with those objects. The sensorimotor system plays a pivotal role in the fundamental cognitive ability of categorization.

Yet, merely affixing cameras or sensors to a machine is insufficient. Vision, like any sensory perception, is an active process that arises from movement. Walking, for instance, involves not just leg movements calculated by the brain but also a profound understanding of body physics. Over millennia of evolution, advanced organisms have honed their control over these motions, leveraging feedback from their bodies.

This exploitation of bodily feedback is not confined to movement. It extends to the realm of language and understanding. The theory of conceptual metaphor reveals that our grasp of language is intimately interwoven with our bodily experiences. Expressions like “hitting a stumbling block” or “biting off more than one can chew” derive their meaning from bodily sensations and encounters.

In light of this, the role of AI models like GPT-3 becomes more nuanced. GPT-3’s impressive language capabilities stem from analyzing trillions of instances, enabling it to generate coherent text, code, and more. However, it falls short of human-like comprehension of language and meaning. For humans, words and sentences acquire meaning through their embodied experiences — actions, perceptions, and emotions. Understanding a term like “paper sandwich wrapper” involves more than just language statistics; it also involves sensory qualities and how we can use the object, which are both influenced by our physical needs and capabilities.

In essence, our physical bodies shape our minds and, by extension, our comprehension of the world. Current AI models, like GPT-3, are still a considerable distance from replicating this depth of understanding. As AI advances and increasingly integrates with the physical world, we confront the possibility of technology surpassing our own embodied intelligence.

In this digital age narrative, we are compelled to ponder our position in a future where the boundaries between artificial and human intelligence blur. Will we, as Steve Wozniak muses, become subservient to our AI creations, or will we discover a new equilibrium in this ever-evolving relationship?.

The path to achieving genuine artificial intelligence intertwines with the journey of robots, their embodiment, sensory experiences, and interaction with the world. These robots are redefining the landscape of AI, forging a future where machine intelligence is more than just algorithms and data — it’s a synergy of sensorimotor learning, embodiment, and a deep connection with the physical world.

Is our body the key to understanding human intelligence?

In the quest to unravel the mysteries of human intelligence, we often find ourselves grappling with profound questions about the intricate relationship between the mind, the body, and our surroundings. We instinctively understand that human cognition transcends a mere catalog of objects; it encompasses writing, reading, political contemplation, scientific inquiry, and even existential ponderings. Yet, remarkably, our bodies remain integral to this complex cognitive tapestry.

Einstein, while conceiving his theory of general relativity, envisioned himself riding a beam of light at the speed of light, highlighting the role of embodiment even in abstract thought. This concept is further explored by George Lakoff and Mark Johnson, who argue that our capacity for abstract thought has its roots in our bodily experiences. According to their theory, fundamental concepts are tied to our bodies and our movements in space, a notion reflected in our everyday language and metaphors. Concepts like “moving ahead with a project” or equating happiness with being “up” illustrate this connection.

Psychological experiments have also revealed how our bodily states can influence our thinking. For instance, the weight of a clipboard can subtly sway our perception of a job candidate’s seriousness. Similarly, the texture of puzzle pieces can impact our evaluation of social interactions. These experiments underline the intricate interplay between our physical sensations and our cognitive processes.

The relationship between our bodies and abstract concepts remains fertile ground for exploration. It suggests that our physicality is an essential component of how we think and understand the world, a concept that has profound implications in the world of artificial intelligence (AI).

In the ever-evolving landscape of AI, a consensus is emerging among researchers: true intelligence, genuine understanding of the world, necessitates a partnership between AI and a physical body — a body that perceives, reacts, and interacts with its environment. The idea of disembodied intelligent minds is being questioned, as it may lead to potentially perilous outcomes. AI devoid of the ability to explore the world, learn from its experiences, and perceive its limitations could pose significant risks and prioritize its objectives over human welfare.

Joshua Bongard and Dr. Boyuan Chen argue that the body is the most important part of being smart and careful, and they support AI that is based on physical embodiments. They argue that intelligence cannot thrive in isolation from the physical realm, and a profound connection between the two is essential.

While some scientists caution against halting AI research, they share concerns about the evolving dangers of advancing technology. Advocates for embodied AI propose a systematic approach that involves continuous real-world trial and error. Beginning with simple robots, they suggest gradually equipping them with more limbs, tools, and capabilities as they demonstrate safe and responsible actions. This iterative exploration in the physical world could pave the way for the emergence of genuine artificial minds.

In contrast to AI models like GPT-3, GPT-4, Bard, Chinchilla, and LLaMA, which lack physical bodies and the ability to independently discern object properties, embodied intelligence seeks to bridge this gap. These models, while impressive, cannot intuit the practical uses of objects or their affordances without the physical experience to guide them. They simulate actions based on text encountered on the internet but lack the nuanced understanding that arises from direct interaction with the physical world.

Imagine a model with access to images as akin to a child learning language and understanding the world through television. While valuable, this mode of learning pales in comparison to the profound understanding that comes from direct interaction with the physical world. This aligns with the principles of embodied cognition, which argue that true comprehension requires active engagement and experience with the world.

In a world where AI is advancing at a rapid pace, the pursuit of embodied intelligence emerges as a compelling path forward. It’s a path that transcends the boundaries between theoretical minds and the physical world, ultimately redefining the future of artificial intelligence.

References:

[1] https://www.nytimes.com/2023/04/11/science/artificial-intelligence-body-robots.html

[2] https://futureoflife.org/open-letter/pause-giant-ai-experiments/

[3] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Embodied_cognition

[4] https://www.nytimes.com/2023/09/18/science/ai-computers-consciousness.html?searchResultPosition=14

[5] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mind–body_problem

[6] https://robohub.org/why-intelligence-requires-both-body-and-brain/

[7] https://gizmodo.com/chatgpt-ai-openai-no-body-no-understanding-1850313233

[8] https://www.nytimes.com/2023/01/28/opinion/chatgpt-ai-technology.html

[9] Does intelligence require a body? https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3512413/pdf/embor2012170a.pdf

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: