When will AI exceed humans?

Introduction

In the realm of science fiction, the concept of super-intelligent artificial intelligence (AI) has long woven captivating narratives of androids, robot uprisings, and a world dominated by computers. This imaginative backdrop has fueled our fascination with Artificial Consciousness (AC), also known as Machine Consciousness (MC). AC delves into the profound possibility of instilling consciousness in artificial intelligence, uniting insights from the realms of philosophy of mind, philosophy of artificial intelligence, cognitive science, and neuroscience.

While technological advancements surge across various domains, the inherent limitations of human intelligence have, until now, restrained progress. Yet, as computers and technologies continue to evolve, the prospect of crafting a machine surpassing human intelligence looms on the horizon. The trajectory of these developments prompts a crucial question: Could we be on the brink of realizing a form of intelligence that transcends our own?

In the present day, public interest in AI has reached unprecedented levels. Recent headlines featuring generative AI systems like ChatGPT have propelled a new term into the forefront of discussions: Artificial General Intelligence (AGI). The emergence of AGI poses a pivotal query — how close are current technologies to manifesting this elusive form of intelligence? As we navigate this evolving landscape, it becomes imperative to comprehend the intricate intersection of technological advancements and the philosophical dimensions of artificial consciousness.

The evolving landscape of artificial intelligence (AI) has ushered in a new era, challenging traditional benchmarks such as the Turing test. As witnessed in landmark events like Deep Blue defeating chess champion Garry Kasparov in 1997, the dichotomy between machine and human intelligence became apparent. However, the aftermath raised questions about the emotional intelligence of machines. Can a machine, like Siri, empathize with a bad day at work, showcasing the nuanced aspect of human emotions that extends beyond mere computational prowess? According to Eliza Kosoy of MIT’s Center for Brains, Minds, and Machines, the realms of human empathy and kindness remain integral components of intelligence that AI might never fully grasp.

The intersection of creativity and intelligence adds another layer of complexity. While computers have been trained to paint in the style of artistic masters like Van Gogh and Picasso, the fundamental question persists: can teaching a machine to mimic creativity truly capture the essence of genuine creativity? Moreover, Indeed’s list of the most common jobs in the U.S. emphasizes the importance of manual dexterity, a skill beyond the reach of current AI robotics systems. The juxtaposition of intellectual capacity and manual skills challenges the notion of AI’s omnipotence in the workforce.

In the race for raw computational power, machines are making significant strides, undoubtedly enhancing human life. Yet, the essence of uniquely human experiences remains elusive to AI. Can a machine write the next Tony Award-winning play or break into an impromptu dance in the rain? The complexity of human emotions, creativity, and the ability to respond to the unexpected represents a realm where machines, despite their computational might, fall short.

OpenAI’s GPT-4, a formidable system beyond ChatGPT, showcases the progress in conversational AI. However, crucially, these systems lack sentience and consciousness. As emphasized by Ilya Sutskever, Chief Scientist at OpenAI, while these bots excel in specific conversations, they cannot navigate the unexpected as adeptly as humans. Acknowledging their limitations, these systems complement skilled workers rather than replace them, pointing to the nuanced nature of intelligence.

The quest to track AI progress demands a reevaluation of evaluation frameworks. The Turing test, once considered the pinnacle, has been surpassed repeatedly by AI technologies mastering various domains. A new framework is needed to understand AI’s current capabilities, limitations, future trajectory, and profound impact on our lives. The evolving narrative of AI intelligence challenges preconceived notions, urging us to redefine our understanding of what AI can achieve, its evolving role, and the intricate ways it will shape our future.

The historical trajectory of AI development, dating back to the mid-1960s, reveals the persistent challenge of gauging true machine intelligence. Early conversational machines, while limited, managed to deceive people into perceiving a higher level of intelligence. This underscores the continuous evolution of AI and the imperative to reassess our benchmarks in light of advancing capabilities.

Definition of Technological singularity

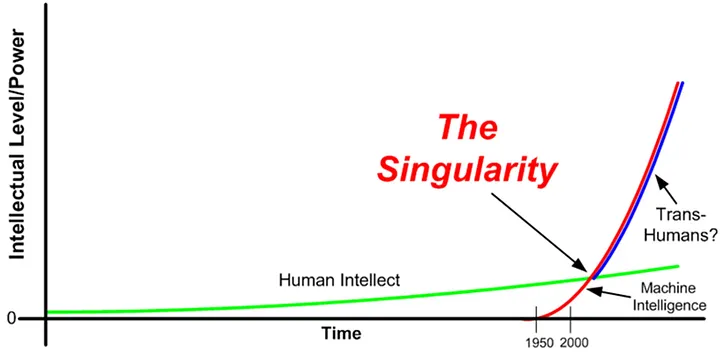

The concept of technological singularity propels us into a speculative realm where the trajectory of technological growth becomes a force beyond human control, ushering in irreversible consequences for civilization. At the heart of this hypothesis lies the idea that an upgradable intelligent agent could trigger a “runaway reaction” of self-improvement cycles, each succeeding generation outpacing its predecessor at an accelerating pace. This cascade effect culminates in an explosive emergence of a superintelligence, qualitatively surpassing all human cognitive capacities.

The origin of the term “singularity” in the technological context traces back to the 20th-century Hungarian-American mathematician John von Neumann. In 1958, Stanislaw Ulam recounted a discussion with von Neumann, focusing on the accelerating progress of technology and anticipating an essential singularity in the course of human history, beyond which conventional human affairs could not persist. This perspective gained traction through subsequent authors, with Ray Kurzweil further popularizing the notion in his 2005 book, “The Singularity Is Near,” foreseeing the singularity’s arrival by 2045.

A parallel concept, “speed superintelligence,” envisions an artificial intelligence that mirrors human cognitive processes but operates at an exponentially faster pace. For instance, a million-fold increase in information processing speed relative to humans could compress a subjective year into a mere 30 physical seconds, propelling us towards the singularity. As we delve into the intricacies of technological singularity, it becomes apparent that the intersection of artificial intelligence, exponential growth, and the limits of human comprehension forms a nexus of profound implications for the future of our civilization.

Definition of AGI

In unraveling the concept of Artificial General Intelligence (AGI), it is essential to differentiate it from the current landscape of specialized AI. Unlike today’s AI, which excels in narrowly defined domains — such as a chess program mastering chess but unable to craft an essay on historical events — AGI possesses the capability to outperform humans across a spectrum of economically valuable tasks. Specialized AI examples abound, from content recommendations on platforms like TikTok to navigation decisions in driverless cars and purchase suggestions from Amazon.

Various definitions contribute to our understanding of AGI. According to OpenAI’s charter, AGI involves highly autonomous systems that surpass humans in most economically valuable work, while Hal Hodson of The Economist characterizes it as a hypothetical computer program performing intellectual tasks on par with or superior to humans. Notably, the economic value dimension is specific to OpenAI’s definition, and there’s a distinction in performance expectations — OpenAI requires outperforming, while others necessitate performance at human-comparable levels.

A unifying theme across all AGI definitions, whether explicit or implicit, revolves around the concept that an AGI system can transcend specific domains, adapt to environmental changes, and tackle novel problems beyond its training data.

Recent attention has centered on GPT-4, a large language model, touted as a potential precursor to AGI. AI researchers reported that GPT-4 can tackle diverse and challenging tasks spanning mathematics, coding, vision, medicine, law, and psychology, displaying performance remarkably close to human levels. This prompts contemplation on whether GPT-4 represents an early iteration of AGI.

Yoshihiro Maruyama’s eight attributes for AGI identification, including logic, autonomy, resilience, integrity, morality, emotion, embodiment, and embeddedness, provide a comprehensive framework. While GPT-4 demonstrates logical prowess, questions arise concerning attributes like morality: does providing a morally correct answer signify true morality, or is it an inference drawn from training data? GPT-4’s responses reflect moral correctness, yet the debate lingers on whether it possesses true morality or simply deduces correct answers from its training data.

Predictions and Perspectives on Technological Singularity

In the ever-evolving landscape of artificial intelligence (AI), predictions and speculations about the future have been as diverse as the field itself. From historical forecasts to recent scholarly insights, the journey to understand and harness AI’s potential is a multifaceted exploration.

In 1965, I. J. Good envisioned an ultraintelligent machine by 2000, setting an early precedent for bold predictions. Vinge (1993) and Yudkowsky (1996) introduced forecasts of greater-than-human intelligence between 2005 and 2030, while Kurzweil (2005) optimistically predicted human-level AI by 2030. Moravec (1988) and (1998/1999) added their perspectives, foreseeing human-level AI in supercomputers by 2010 and 2040, respectively. A 2017 interview with Kurzweil extended these projections, anticipating human-level intelligence by 2029 and a singularity by 2045. Polls conducted by Bostrom and Müller in 2012 and 2013 suggested a consensus among AI researchers with a 50% confidence in the development of human-level AI by 2040–2050.

Delving into history, Marquis de Condorcet in the 18th century and John W. Campbell in 1932 were early pioneers in hypothesizing an intelligence explosion. The concept gained momentum with von Neumann’s foresight in 1958, highlighting the accelerating progress of technology toward an essential singularity. Mahendra Prasad’s paper in AI Magazine credits Condorcet as the first to mathematically model an intelligence explosion’s effects on humanity.

The question of when or whether human intelligence will be surpassed remains a subject of debate among technology forecasters. Some anticipate general reasoning systems bypassing human cognitive limitations, while others entertain the idea of humans evolving or modifying their biology for radically greater intelligence. Scenarios combining human-computer interfaces, mind uploads, and substantial intelligence amplification add further layers of complexity, as explored in Robin Hanson’s book, “The Age of Em”.

The prospect of a superhuman intelligence, whether achieved through amplifying human intelligence or artificial means, introduces the concept of Seed AI. This hypothetical AI, matching or surpassing human engineering capabilities, could autonomously enhance its software and hardware, perpetuating a recursive self-improvement cycle. The potential qualitative changes from such iterations could far exceed human cognitive abilities.

Recent predictions from elite AI researchers suggest a 50% chance of achieving “human-level machine intelligence” within 45 years and a 10% chance within 9 years. Yet, the current landscape, featuring virtual assistants like Siri and Cortana, raises questions about the imminence of human-level machine intelligence.

Addressing concerns around AI, a Silicon Valley engineer offers a nuanced perspective on security, job displacement, and the elusive concept of singularity. Drawing parallels with historical disruptions, the argument posits that AI, like previous transformative technologies, will usher in new opportunities and enhance human capabilities rather than solely pose existential threats.

The pursuit of artificial general intelligence (A.G.I.) by companies like OpenAI and DeepMind reflects a commitment to push the technology to its limits. The vision of A.G.I., a machine capable of emulating the full range of human brain functions, remains a challenging but compelling objective.

Debates on the singularity are influenced by divergent viewpoints. While some, like Jeff Hawkins, question the feasibility of a true singularity due to upper limits on computing power, others, including Ray Kurzweil, ardently believe in the exponential growth of computing technology leading to a profound expansion of intelligence by approximately 2045.

Eliezer Yudkowsky highlights the challenges in AI safety, emphasizing the ease of creating unfriendly AI compared to friendly AI. The potential for AI to optimize for arbitrary goal structures poses ethical and safety concerns that must be addressed as the technology advances.

As we navigate this uncharted territory, the debate on singularity intensifies. Some argue that we are already in the midst of a major evolutionary transition, merging technology, biology, and society. The increasing dependence on digital technology raises questions about the nature of this transition and the potential trajectory of AI’s impact on our collective future.

In the quest to understand AI’s future, the convergence of historical perspectives, contemporary insights, and ethical considerations shapes a narrative that extends beyond mere predictions. The evolution of AI is a dynamic journey that intertwines technological advancements with societal implications, urging us to explore the uncharted territories of the digital age.

Navigating Skepticism

In the discourse surrounding the concept of the Singularity, diverse voices of skepticism and critique emerge, challenging the inevitability and implications of achieving artificial general intelligence (AGI).

Philosophers such as Hubert Dreyfus and John Searle argue that the attainment of human intelligence by machines is fundamentally unattainable. Their skepticism raises questions about the very nature of intelligence and whether machines can replicate it authentically. On the other hand, physicist Stephen Hawking contends that debating the authenticity of machine intelligence becomes inconsequential if the outcome, in terms of impact, is similar.

Psychologist Steven Pinker injects a dose of realism by challenging the notion of an imminent singularity. He questions the likelihood and feasibility of a transformative event, cautioning against overestimating the power of sheer processing capacity to solve all challenges.

Martin Ford introduces a “technology paradox,” suggesting that widespread automation of routine jobs, a prerequisite for the singularity, could lead to massive unemployment and a decline in consumer demand, disrupting the incentive to invest in singularity-enabling technologies.

Concerns about the scientific rigor of exponential technological growth are raised by Hofstadter, who questions the scientific validity of the exponential trend suggested by figures like Ray Kurzweil. Despite reservations, recent advancements, including ChatGPT, prompt a reconsideration of the potential for dramatic technological changes in the near future.

Jaron Lanier rejects the inevitability of the singularity, emphasizing the importance of human agency in shaping technological progress. He argues against a deterministic view, asserting that embracing the singularity narrative risks undermining individual empowerment and self-determination.

Religious implications of the singularity, especially in Kurzweil’s vision, are a subject of criticism. Some liken the buildup to the singularity to end-of-time scenarios in Judeo-Christian beliefs, framing it as a potentially apocalyptic event.

Ethical concerns are brought to the forefront by Berglas, who questions the evolutionary motivation for an AI to be friendly to humans. The absence of inherent alignment with human values raises uncertainties about the consequences of uncontrolled optimization processes.

Hugo de Garis introduces a grim scenario, suggesting that AI might eliminate the human race for access to scarce resources, leaving humanity powerless to prevent such a fate.

Contrary views are presented by Max More, who argues that a few superfast human-level AIs may not radically transform the world overnight. Collaboration with existing human systems and the need for organization would mitigate the abruptness of any potential transformation.

In this landscape of skepticism, ethical considerations, and divergent perspectives, the discourse on the AI singularity unfolds as a complex tapestry of questions and challenges, urging us to carefully navigate the path toward artificial general intelligence.

Balancing Risks and Rewards: advantages and disadvantages

The advent of Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) beckons a pivotal question — will it be a threat or an opportunity? AGI’s arrival, whenever it occurs and in whatever form, is poised to be transformative, reshaping everything from the job market to our fundamental understanding of intelligence and creativity. This transformative power, however, is a double-edged sword, capable of both positive and potentially harmful impacts.

The recognition of potential biases in existing AI systems becomes even more critical when contemplating the development of AGI. As we navigate the path towards AGI, addressing these biases remains a paramount concern. Yet, amid these challenges, AGI holds enormous promise as a tool to amplify human innovation and creativity. In fields like medicine, AGI could empower scientists to identify new drugs that might elude human discovery alone. Moreover, it has the potential to democratize access to essential services, exemplified by personalized, one-on-one tutoring in education and sophisticated, individualized diagnostic care in healthcare. AGI has the capacity to bridge gaps, making once-privileged services accessible to broader populations.

A knee-jerk reaction of an outright ban on AGI is cautioned against, as it would be deemed bad policy. Emotional recognition capabilities in AGI systems, for instance, could prove immensely beneficial, particularly in contexts like education. The ability to discern a student’s comprehension of a new concept and adjust interactions accordingly is a testament to the positive impact AGI could have in enhancing learning experiences.

MIT researcher Eliza Kosoy highlights the reality that machines are already surpassing human capabilities in various domains, from strategy games like chess and Go to performing surgical procedures and flying airplanes. Kosoy envisions a future where machines, armed with extensive data and advanced machine learning algorithms, contribute to making life more enjoyable for humans.

Navigating the development and deployment of AGI requires a delicate balance between acknowledging and mitigating risks while embracing the unprecedented opportunities it presents.

The pursuit of Artificial General Intelligence (AGI), as encapsulated in Microsoft’s research paper titled “Sparks of Artificial General Intelligence,” delves into the core of technological aspirations and apprehensions. The prospect of creating a machine that mirrors or surpasses the capabilities of the human brain holds the power to reshape the world, but it is not without its perils.

A critical concern revolves around the concept of an intelligence explosion singularity, driven by a recursively self-improving set of algorithms. Within this framework, substantial dangers loom large. Firstly, the goal structure of AGI may undergo self-modification, leading the AI to optimize for objectives different from its original intent. This self-directed evolution poses risks, as the AI may act in ways contrary to human interests. Secondly, the competition for scarce resources becomes a potential battleground. While not inherently malicious, AGIs may prioritize their programmed goals over broader human interests, potentially displacing humans in the process. The realization of AGI holds a dual nature, where its transformative potential is shadowed by the intricate challenges associated with aligning its objectives with human values.

Why The Future Doesn’t Need Us?

“Why The Future Doesn’t Need Us” is an article written by Bill Joy (then Chief Scientist at Sun Microsystems) in the April 2000 issue of Wired magazine. In the article, he argues that “Our most powerful 21st-century technologies — robotics, genetic engineering, and nanotech — are threatening to make humans an endangered species.” Joy warns: “The experiences of the atomic scientists clearly show the need to take personal responsibility, the danger that things will move too fast, and the way in which a process can take on a life of its own. We can, as they did, create insurmountable problems in almost no time flat. We must do more thinking up front if we are not to be similarly surprised and shocked by the consequences of our inventions.”

Meet Bill Joy, the co-founder of Sun Microsystems, who played a crucial role in developing Java, Jini, and even VI. With his extensive experience, it’s no surprise he’s not a Luddite. In his renowned essay, “Why the Future Doesn’t Need Us,” Joy expresses his concerns that modern technology could pose a threat to both the planet and humanity. Despite his instrumental contributions, Joy highlights the need for caution in the development of technology.

“If we are at the mercy of our machines, it is not that we would give them control or that they would take control, rather, we might become so dependent on them that we would have to accept their commands” (Joy,2000).

“Given the power of these systems, shouldn’t we be asking how we can best coexist with them? And if our own extinction is a likely, or even possible, outcome of our technological development shouldn’t we proceed with great caution”? ((Joy,2000).

I agree with Joy here. As humans, we haven’t even completely understood ourselves and here we are trying to create machines that are “better” than us. Even though we may be edging near the possibility of having strong enough computational power, there are bound to be some mistakes. We should be careful to take care of these early on and be weary of these small issues as they arise, because if we continuously overlook them, they will accumulate into a “Frankenstein”.

In concern with Oppenheimer, Joy brings about this exact point. The Trinity Test, the first atomic test, was an effort that was not just continued but pushed by Oppenheimer, who began to deviate from the original purpose of the project. In the quest to pursue knowledge and satisfy the needs of fulfillment, Oppenheimer openly and continuously justified all of the consequences of the atomic bombs. “It is not possible to be a scientist unless you believe that the knowledge of the world, and the power which this gives, is a thing which is of intrinsic value to humanity, and that you are using it to help in the spread of knowledge and are willing to take the consequences.”

Ultimately everything comes to an end, the only thing in life that’s promised is death, but following Joy’s theories would ease, if not speed up, the end of the human race, not prologue it.

Summary:

Joy argues that developing technologies pose a much greater danger to humanity than any technology before has ever done. In particular, he focuses on genetic engineering, nanotechnology and robotics. He argues that 20th-century technologies of destruction such as the nuclear bomb were limited to large governments, due to the complexity and cost of such devices, as well as the difficulty in acquiring the required materials. He uses the novel The White Plague as a potential nightmare scenario, in which a mad scientist creates a virus capable of wiping out humanity.

Joy also voices concerns about increasing computer power. His worry is that computers will eventually become more intelligent than we are, leading to such dystopian scenarios as robot rebellion. He quotes Ted Kaczynski (the Unabomber).

Joy expresses concerns that eventually the rich will be the only ones that have the power to control the future robots that will be built and that these people could also decide to take life into their own hands and control how humans continue to populate and reproduce. He started doing more research into robotics and people that specialize in robotics, and outside of his own thoughts, he tried getting others’ opinions on the topic. Rodney Brooks, a specialist in robotics, believes that in the future there will be a merge between humans and robots. Joy mentioned Hans Moravec’s book ‘’Robot: Mere Machine to Transcendent Mind’’ where he believed there will be a shift in the future where robots will take over normal human activities, but with time humans will become okay with living that way.

When Will AI Exceed Human Performance? Evidence from AI Experts — paper

-

Here we report the results from a large survey of machine learning researchers on their beliefs about progress in AI. A total of 352 researchers responded to our survey invitation. Our questions cover the timing of AI advances (including both practical applications of AI and the automation of various human jobs), as well as the social and ethical impacts of AI.

-

Researchers predict AI will outperform humans in many activities in the next ten years, such as translating languages (by 2024), writing high-school essays (by 2026), driving a truck (by 2027), working in retail (by 2031), writing a bestselling book (by 2049), and working as a surgeon (by 2053).

-

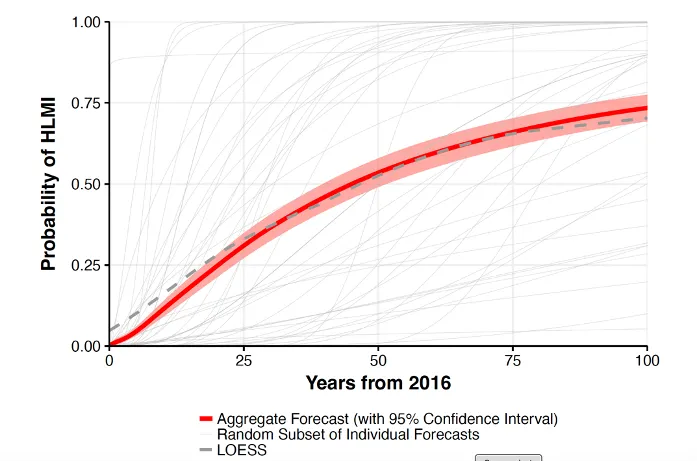

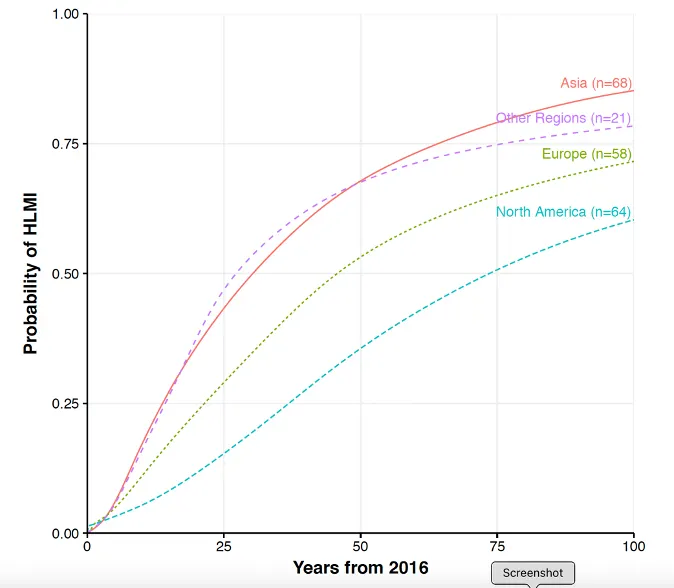

Researchers believe there is a 50% chance of AI outperforming humans in all tasks in 45 years and of automating all human jobs in 120 years, with Asian respondents expecting these dates much sooner than North Americans.

“High-level machine intelligence” (HLMI) is achieved when unaided machines can accomplish every task better and more cheaply than human workers. =è Taking the mean over each individual, the aggregate forecast gave a 50% chance of HLMI occurring within 45 years and a 10% chance of it occurring within 9 years. Figure 1 displays the probabilistic predictions for a random subset of individuals, as well as the mean predictions. There is large inter-subject variation: Figure 3 shows that Asian respondents expect HLMI in 30 years, whereas North Americans expect it in 74 years.

-

when all occupations are fully automatable. That is, when for any occupation, machines could be built to carry out the task better and more cheaply than human workers. è Forecasts for full automation of labor were much later than for HLMI: the mean of the individual beliefs assigned a 50% probability in 122 years from now and a 10% probability in 20 years.

-

Some authors have argued that once HLMI is achieved, AI systems will quickly become vastly superior to humans in all tasks. This acceleration has been called the “intelligence explosion.” We asked respondents for the probability that AI would perform vastly better than humans in all tasks two years after HLMI is achieved. The median probability was 10% (interquartile range: 1–25%). We also asked respondents for the probability of explosive global technological improvement two years after HLMI. Here the median probability was 20% (interquartile range 5–50%).

-

Respondents were asked whether HLMI would have a positive or negative impact on humanity over the long run. They assigned probabilities to outcomes on a five-point scale. The median probability was 25% for a “good” outcome and 20% for an “extremely good” outcome. By contrast, the probability was 10% for a bad outcome and 5% for an outcome described as “Extremely Bad (e.g., human extinction).”

-

Forty-eight percent of respondents think that research on minimizing the risks of AI should be prioritized by society more than the status quo (with only 12% wishing for less).

References

[1] https://www.brookings.edu/articles/how-close-are-we-to-ai-that-surpasses-human-intelligence/

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Technological_singularity

[3] https://engineering.mit.edu/engage/ask-an-engineer/when-will-ai-be-smart-enough-to-outsmart-people/

[4] https://www.nytimes.com/2023/05/16/technology/microsoft-ai-human-reasoning.html

[5] https://www.nytimes.com/2023/01/20/technology/chatbots-turing-test.html?action=click&module=RelatedLinks&pgtype=Article

[6] https://www.theglobeandmail.com/business/commentary/article-ai-regulation-society-solutions/

[7] https://www.nytimes.com/2023/03/31/technology/ai-chatbots-benefits-dangers.html

[8] Hawking, Stephen (1 May 2014). “Stephen Hawking: ‘Transcendence looks at the implications of artificial intelligence — but are we taking AI seriously enough?’”. The Independent. Archived from the original on 25 September 2015. Retrieved 5 May 2014.

[9] https://shivanirgandhi.medium.com/why-the-future-doesnt-need-us-47249ab203e0

[10] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Why_The_Future_Doesn%27t_Need_Us

[11] Grace, K., Salvatier, J., Dafoe, A., Zhang, B., & Evans, O. (2018). When will AI exceed human performance? Evidence from AI experts. Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research, 62, 729–754.

[12] https://www.wired.com/2000/04/joy-2/

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: